About | Portfolio | Script Archive | Blog | Newsletter

Small towns, modern loneliness

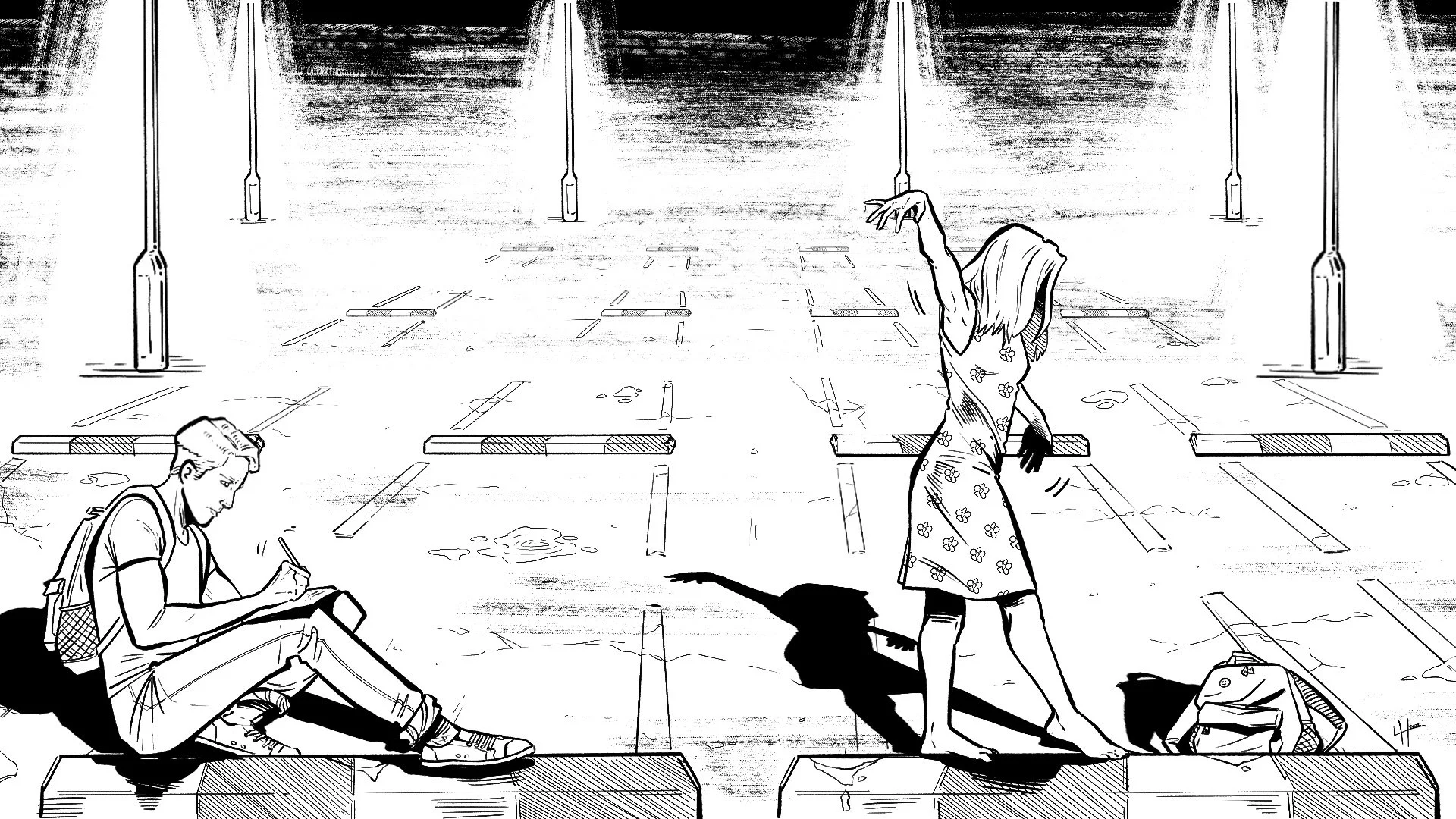

Written by Michael Kurt | Illustration by Laura Helsby

Hailey Serton’s mother annoyed the shit out of her. Despite the many years they’d spent living in a small apartment, they had not become bonded by their shared experience of her teenage life. So when she got home late from the Melville Shakespeare Festival, Hailey gave the living room a wide berth in hopes that the undoubtedly strong smell of cigarettes could not be detected on her summer dress.

“Did you have a good time?” her mother called, turning away from what she was watching on the living room TV.

She had not had a good time, actually, but was too tired and too dirty to be trapped in a conversation about it. “Sure,” she called back.

There was a pretentiousness to anything Shakespearean around which Hailey could never fully relax, despite many years of community and high school theater. Fern Michaels, who had asked her to take the bus with him to Melville, thought she might like it, which, given the kind of person she was, was not entirely surprising, but deeply disheartening.

Hailey’s mother followed her almost all the way into the bathroom. “How was the bus?”

“It was a long trip. Especially back,” she replied, closing the door.

When Hailey met Fern last year, she was quickly able to convince him to wait with her in the parking lot after rehearsals. Her mother was chronically late and Fern was chronically lonely, so she was doing him a favor. What she did not expect, however, was that Fern’s mother would circle the school for a half hour before finally offering to drive her home. So, by the time Fern asked her to go to the festival with him, she felt that she’d owed him many times over.

Through the bathroom door, Hailey’s mother asked: “Did he try anything?”

“Who?”

“That boy.” Her mother didn’t like his name, and avoided saying it. “Fern, or whatever.”

“Did Fern try anything at the Shakespeare Festival in the middle of a crowd of theater dorks?” Hailey traced what looked like Central America in dirt on her leg and noticed a burn mark on one of her socks, which was regrettable, but fine. “No. He didn’t try anything,” she said, and wondered for the first time why he didn’t go by his middle name, which was Thomas.

Hailey started the shower and, from the living room, could faintly make out the theme song of her mother’s favorite show.

Fern was not the kind of person she saw developing feelings for. He was talented, for a young playwright, but too timid to feel comfortable around. When he joined the drama club, Hailey knew it was because he would have otherwise had to be home with his parents. Like many young people before him, the late-into-the-night and the far-from-my-parents element theater provided was infinitely appealing. Not to mention the cast parties and the dark backstages and the rafters.

It wasn’t that the festival was bad, it was just boring. Too hot for too long with too many boring plays to smoke through. She’d made herself sick within the first hour and wanted to drink something that made her feel weightless. She wanted to roll on ecstasy and dip tobacco, she wanted to trip on acid, she wanted to be off her rocker. But every time she thought about being out of control she thought about death and getting lost in Melville. It was dangerous at the festival; too many romantics. Too many outstretched hands with foam-core skulls and candelabras. Too much poison.

There was also, somewhere in the back of her mind, the fear that Fern might try to kiss her.

On her apartment’s doorstep, they were close enough to her to kiss. She closed her eyes, bracing for what was bound to be an incredibly awkward moment. But nothing happened, which was probably for the best because soon she would leave for summer camp and knew she would end up making out with one of her fellow camp counselors. For many years, she’d feared that if any romance had not first been funneled through a thick aura of pine needles and summer stars, then it would lack any purpose at all. No smoke, no fire.

“I had a nice time,” she said, and put on her best stage smile.

“Yeah, it was,” he said, but didn’t move, “nice.”

“I should get inside,” she said, unlocking the door. “My mom’s probably pissed.”

“Have a good night,” Fern said, from what felt like the other side of the street. “I’ll text you later.”

Inside, in the shower, finally feeling like she was not entirely made of dirt, Hailey found herself thinking about the characters Fern wrote for her to play. They were bold and sad; they kept secrets from their friends; they were cute and popular, but in trouble. They watched old sitcoms on their laptop before bed. They were often alone.

From inside her purse, on the floor of the bathroom, her phone vibrated. Two text messages.

“Did you eat?” her mother asked through the door.

“Yes,” she answered, quickly. It was almost midnight; too late for anything but the potato chips and warm cans of soda she hid in her room.

“I made a recipe from the NYTimes,” her mother said. Then, faintly: “It almost looks like the picture.”

“I’ll have some tomorrow,” Hailey replied, accidentally pressing her cheek to the shower curtain, which had a cold, strange feeling.

“I’ll put it in foil then?” her mother asked. But Hailey didn’t answer. She filled her ears with water and allowed herself to escape, into deafness. When she was fourteen she was invited to her first cast party. It was at someone named Dave’s house, and when she arrived there was no doubt that Dave had the house of someone with famous parents; it was very nice. The kind of nice you should definitely not invite a bunch of your freshmen castmates to. But, alas, they swam.

Here are the people I’ll know for the rest of my life, she thought. The next generation of young actors, spitting pool water and swimming in their shirts. During camp, earlier that summer, Hailey had joined some junior counselors behind one of the cabins for what would be the first of many late night cigarettes. But at the party, it was more than cigarettes. There was a palpably lost feeling as she entered Dave’s backyard and, as she let herself sink to the bottom of the pool, all of the sounds became a muffled nothingness. Truly quiet.

She ended up leaving before everyone else, citing how her mom would be up waiting and how they had early classes. But, despite the thrill of being out late and around her older castmates, she was happier at home. She later heard that more than one of the play’s understudies ended up in the shower with all their clothes on and that, after stealing an entire case of beer from the 7-Eleven, Henry Denauhe crashed his dad’s Honda Civic. He’d be alright, they said, but grounded for life.

As she turned off the water, the bathroom became cold and then sticky with a humidity rare to Oregon summers.

It wasn’t that bad, living with her mother, but Hailey knew she would lose any ability to stay level-headed if confronted by even a short round of questions. Who was there, where were they from, was it safe, and, of course, were you smoking cigarettes? How many? Where from? Who for? And so on.

There would be plenty of time for these, and many more questions, on the drive to Camp Timber View. Until then, Hailey planned to spend as much time as possible out “seeing friends” on her “last few days in town.” But in truth, she would be riding the bus around town alone—to the mall, to the community theater building, to the backstage rooms of her high school theater wing, which were actually just storage closets with desks and mirrors, but nevertheless made them feel like real performers.

During her sophomore year, the band gave up the gym rehearsal spaces in favor of new trailers the school brought in to solve the problem of overcrowding. The trailers quickly became an oasis for band and punk kids, largely due to their distance from the rest of the school (and teachers), and devolved into a brass and drum-heavy autonomous zone. Hailey tried, at one point, to integrate herself into this paradise, but found the loudness overwhelming. In a closet, which was meant to store the red and yellow marching band outfits, Marsha Herron begged her not to leave.

“You can’t! I’ll be alone with them,” she cried, in a way that was not quite believable. “They touch each other.”

Hailey laughed because it was true. “So cliche.”

They drank from a liter bottle of orange soda that had been topped off with gin and then slowly warmed in Marsha’s backpack, handing it back and forth between them. “It’s not even fun anymore.”

“You could always join the drama club,” Hailey offered.

“Ew, no.” Marsha took a sip that Hailey was pretty sure was performative. “I’d rather be in A.V., to be honest.”

In less than two weeks, though, Hailey had had enough of the band trailers. “I’d rather be home,” she sent as a text to Marsha, “and that says a lot.”

One of the last assignments she did for high school was for creative writing. Her favorite teacher, Mrs. Rose, asked the class to create a story without using words. A lot of her classmates took it seriously, which surprised Hailey because a lot of her classmates were idiots. She spent the week tracing back through all of the places she never wanted to see again, but nevertheless knew she would miss someday. She took pictures with her Canon point and shoot, and photocopied them into a zine, knowing that it would come in handy at her fancy arts college. There’s no way they could resist, she thought. She’d win awards and speak deeply about her small town, modern loneliness. Then, after everyone left, she’d watch Gilmore Girls and eat ramen chips from the Asian market. If this is the future, then I’ll be happy, she thought. If only.

The messages from Fern were: Thanks for coming with me and I know you hate The Bard.

Despite wanting very badly to leave, and to not have a picturesque moment with Fern, she knew she would regret the untied knot of their friendship. There would be some time before they saw each other again—maybe even a year—and, without making explicit promises, Hailey knew it would be nice to see him. Fern was a year younger and, therefore, would still be writing plays in the dark wings of the high school theater while she was away at college. He promised to take Mrs. Rose for Creative Writing and to send her all the writing prompts he received. He promised to take pictures.

Hailey turned her phone to silent and closed her eyes. She tried not to think of Shakespeare, but knew she would dream about the festival and the bus ride back and Fern on the doorstep of her apartment building, waiting. Summer camp, she willed into her dreams, far away. If I can make it to summer camp, I’ll be free.

June 2022 is a piece of fiction, written by Michael Kurt, whose work includes the short comics Halloween and Sinkhole.

The Illustration for June 2022 was done by Laura Helsby, who is an illustrator and comic book artist from Manchester UK, specializing in black and white inked work. They love anything horror, as well as vintage cassette tapes and vinyl records, especially punk.